- Home

- John Howard Griffin

Black Like Me

Black Like Me Read online

A BOOK FOR OUR TIME

Studs Terkel tells us in his Foreword to the definitive Griffin Estate Edition of Black Like Me: “This is a contemporary book, you bet.” Indeed. Black Like Me is required reading in thousands of high schools and colleges for this very reason. Regardless of how much progress has been made in eliminating outright racism from American life. Black Like Me endures as a great human - and humanitarian - document. In our era, when “international” terrorism is most often defined in terms of a single ethnic designation and a single religion, we need to be reminded that America has been blinded by fear and racial intolerance before. As John Lennon wrote, “Living is easy with eyes closed.” Black Like Me is the story of a man who opened his eyes, and helped an entire nation to do likewise.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Known primarily as the author of the modern classic. Black Like Me, John Howard Griffin (1920-1980) was a true Renaissance man. He fought in the French Resistance and served in the Army-Air Force in the South Pacific during World War II. Griffin became an acclaimed novelist and essayist, a remarkable portrait photographer and a musicologist recognized as an expert on Gregorian Chant.

On October 28, 1959, John Howard Griffin dyed himself black and began an odyssey of discover] through the segregated Deep South. The result was Black Like Me. arguably the single most important documentation of 20th century American racism ever written.

Because of Black Like Me, Ggiffin was personally vilified, hanged in effigy in his hometown, thrreatened with deatd, and – asl late as 1975 – severely beaten by the KKK. Griffin’s courageous act and the book it generated earned him international respect as ha human rights activist. griffin worked with Martin Luther King, Dick Gregory, Saul Alinsky, and NAACP Director Roy Wilkins throughout the Civil Rights era. He taught at the University of peace with Nobel Peace Laureate Father Dominique Pire, and delivered more than a thousand lectures in Europe, Canada and the US.

Earlier, during a decade of blindness (1947-1957), Griffin wrote nobels. his 1952 bestseller, The Devil Rides Outside, was a test case in a controversial trial before the US Supreme Court that resulted in a landmark decision against censorship. Two of his most important books have been published posthumously as part of a growing revival of interest in griffin’ work: Street of the Seven Angels, a satiric anti-censorship movel, and Scatterd Shadown: A Memoir of Blindness and Vision.

Works by John Howard Griffin

The Devil Rides Outside (1952, Ebook 2010)

Nuni (1956, Ebook 2010)

Land of the High Sky (1959)

Black Like Me (1961)

The Definitive Griffin Estate Edition (2004)

The Definitive Griffin Estate Edition, Revised with Index (2006)

Ebook edition (2010)

50th Anniversary Edition (2011)

The John Howard Griffin Reader (1968)

The Church and the Black Man (1969)

A Hidden Wholeness: The Visual World of Thomas Merton (1970)

Twelve Photographic Portraits (1973)

Jacques Maritain: Homage in Words and Pictures (1974)

A Time to Be Human (1977)

The Hermitage Journals (1981)

Follow the Ecstasy: Thomas Merton’s Hermitage Years (1983, 1993, Ebook 2010)

Pilgrimage (1985)

Encounters with the Other (1997)

Street of the Seven Angels (2003, Ebook 2010)

Available Light: Exile in Mexico (2008, Ebook 2010

Scattered Shadows: A Memoir of Blindness and Vision (2004, Ebook 2010)

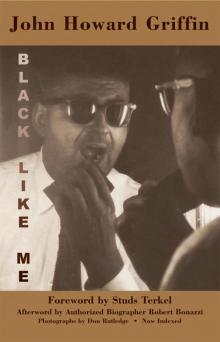

“I wet my sponge, poured dye on it, and touched up the corners of my mouth and lips, which were always difficult spots.”

- Black Like Me, page 119

This photograph of Griffin applying the “dye” to his face is here published for the first time. This and other historic photographs included in this edition of Black Like Me were taken by Don Rutledge in 1959 in New Orleans.

Black Like Me © 1960, 1961, 1977 by John Howard Griffin.

Portions first appeared in Sepia magazine © 1960 by Good Publishing Co. Copyright renewed 1989 by Elizabeth Griffin-Bonazzi, Susan Griffin-Campbell, John H. Griffin, Jr., Gregory P. Griffin and Amanda Griffin-Fenton. Black Like Me: The Definitive Griffin Estate Edition © 2004 by The Estate of John Howard Griffin and Elizabeth Griffin-Bonazzi. “Beyond Otherness” by John Howard Griffin first appeared in Encounters with the Other (Latitudes Press) © 1997 by Robert Bonazzi. Foreword © 2004 by Studs Terkel. Afterword © 2004 by Robert Bonazzi. Photographs © 2004 by Don Rutledge. Black Like Me: The Definitive Griffin Estate E-Book Edition © 2010 by The Estate of John Howard Griffin and Elizabeth Griffin-Bonazzi. All rights reserved.

First Wings Press Edition, 2004

Second Wings Press Edition, with Index, 2006

ISBN: 0-930324-72-2 (trade hardcover edition) 978-0-930324-72-8

ISBN: 0-930324-73-0 (reinforced library binding) 978-0-930324-73-5

Wings Press Ebook Editions, 2010:

ePub ISBN: 978-1-60940-108-5 • Kindle ISBN: 978-1-60940-109-2

Library PDF ISBN: 978-1-60940-110-8

Except for fair use in reviews and/or scholarly considerations, no portion of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of Robert Bonazzi, representing the Estate of John Howard Griffin and Elizabeth Griffin-Bonazzi.

Wings Press

627 E. Guenther • San Antonio, Texas 78210

Phone/fax: (210) 271-7805 • www.wingspress.com

Distributed by Independent Publishers Group • www.ipgbook.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data:

Griffin, John Howard, 1920 − 1980

Black like me : the definitive Griffin estate edition, corrected from original manuscripts / John Howard Griffin; with a foreword by Studs Terkel; historic photographs by Don Rutledge; and an afterword by Robert Bonazzi.– 1st Wings Press ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-930324-72-2 / 978-0-930324-72-8 (alk. paper) – ISBN

0-930324-73-0 / 978-0-930324-73-5 (reinforced lib. bdg. : alk. paper)

1. African Americans-Southern States-Social conditions. 2. Southern States-Race relations. 3. Griffin, John Howard, 1920- 1980. 4. Texas-Biography. I. Title.

E185.61.G8 2006

975’.00496073–dc22

2004001549

In Memory of

John Howard Griffin (1920-1980)

and

Elizabeth Griffin-Bonazzi (1935-2000)

Contents

Foreword, by Studs Terkel

Black Like Me

Preface, 1961

Deep South Journey, 1959

Photographs by Don Rutledge

The Aftermath, 1960

Epilogue, 1976

Beyond Otherness, 1979

Afterword, 2006, by Robert Bonazzi

Notes

Acknowledgments

Index

Special ebook added content:

Critical Praise for Black Like Me

Foreword

Reading Black Like Me 45 years after it originally appeared is much like walking with a ghost. It is a journey through a haunted land with no cicerone to show you the way. Much has changed during those tumultuous years, especially in the South, and yet much has remained the prickly same. The black-white matter is still the Great American Obsession.

What is it like to be the Other? A few, very few, thoughtful heroic whites, through the four centuries since the arrival of the first slave ship at Charleston Harbor, have at one time or another considered the idea. It was one man who actually followed through. John Howard Griffin, a white Texan, thought the unthinkable and did the undoable: he became a black man.

Griffin, a stude

nt of theology and disciple of Jacques Maritain, a musicologist, photographer and a novelist, decided to become a Negro. (The phrase African-American had not yet enriched our vocabulary).

With the help of a dermatologist, he ingested pigment-changing medicines and subjected himself to intense ultra-violet rays. Though he, in the process, suffered considerable discomfort, he finally “passed.” To add the final touch, he shaved his head clean bald and had, indeed, become an approaching-middle-aged black man of some dignity. He was all set to wander across the Deep South, especially Mississippi. His book is in the form of a diary. The first entry: October 28, 1959. That was the day he became possessed by the challenge. The final one: December 15. That was the day he returned home to his family in Mansfield, Texas as a white husband and father.

What follows is an epilogue; a recounting of the firestorm that ensued with the publication of Black Like Me. He was celebrated, of course, in national journals as well as on TV and radio. The vilification came along with it. It was a matter of course. What mattered most, and still matters most, is the difficulty white Americans have in feeling what it is to be the Other.

A black woman I know speaks of “the feeling tone.” John Howard Griffin, in his perilous, humiliating, and at times hilarious, yet, strangely enough, hopeful adventure, captured “the feeling tone” as no white man I’ve ever known.

This is a contemporary book, you bet.

- Studs Terkel

Chicago, 2004

Preface

This may not be all of it. It may not cover all the questions, but it is what it is like to be a Negro in a land where we keep the Negro down.

Some whites will say this is not really it. They will say this is the white man’s experience as a Negro in the South, not the Negro’s.

But this is picayunish, and we no longer have time for that. We no longer have time to atomize principles and beg the question. We fill too many gutters while we argue unimportant points and confuse issues.

The Negro. The South. These are the details. The real story is the universal one of men who destroy the souls and bodies of other men (and in the process destroy themselves) for reasons neither really understands. It is the story of the persecuted, the defrauded, the feared and the detested. I could have been a Jew in Germany, a Mexican in a number of states, or a member of any “inferior” group. Only the details would have differed. The story would be the same.

This began as a scientific research study of the Negro in the South, with careful compilation of data for analysis. But I filed the data, and here publish the journal of my own experience living as a Negro. I offer it in all its crudity and rawness. It traces the changes that occur to heart and body and intelligence when the so-called first-class citizen is cast on the junk heap of second-class citizenship.

—John Howard Griffin, 1961

Rest at pale evening …

A tall slim tree …

Night coming tenderly

Black like me.

—Langston Hughes

from “Dream Variation”

Deep South Journey

1959

October 28, 1959

For years the idea had haunted me, and that night it returned more insistently than ever.

If a white man became a Negro in the Deep South, what adjustments would he have to make? What is it like to experience discrimination based on skin color, something over which one has no control?

This speculation was sparked again by a report that lay on my desk in the old barn that served as my office. The report mentioned the rise in suicide tendency among Southern Negroes. This did not mean that they killed themselves, but rather that they had reached a stage where they simply no longer cared whether they lived or died.

It was that bad, then, despite the white Southern legislators who insisted that they had a “wonderfully harmonious relationship” with Negroes. I lingered on in my office at my parents’ Mansfield, Texas, farm. My wife and children slept in our home five miles away. I sat there, surrounded by the smells of autumn coming through my open window, unable to leave, unable to sleep.

How else except by becoming a Negro could a white man hope to learn the truth? Though we lived side by side throughout the South, communication between the two races had simply ceased to exist. Neither really knew what went on with those of the other race. The Southern Negro will not tell the white man the truth. He long ago learned that if he speaks a truth unpleasing to the white, the white will make life miserable for him.

The only way I could see to bridge the gap between us was to become a Negro. I decided I would do this.

I prepared to walk into a life that appeared suddenly mysterious and frightening. With my decision to become a Negro I realized that I, a specialist in race issues, really knew nothing of the Negro’s real problem.

October 29

I drove into Fort Worth in the afternoon to discuss the project with my old friend George Levitan. He is the owner of Sepia, an internationally distributed Negro magazine with a format similar to that of Look. A large, middle-aged man, he long ago won my admiration by offering equal job opportunities to members of any race, choosing according to their qualifications and future potentialities. With an on-the-job training program, he has made Sepia a model, edited, printed and distributed from the million-dollar Fort Worth plant.

It was a beautiful autumn day. I drove to his house, arriving there in mid-afternoon. His door was always open, so I walked in and called him.

An affectionate man, he embraced me, offered me coffee and had me take a seat. Through the glass doors of his den I looked out to see a few dead leaves floating on the water of his swimming pool.

He listened, his cheek buried in his fist as I explained the project.

“It’s a crazy idea,” he said. “You’ll get yourself killed fooling around down there.” But he could not hide his enthusiasm.

I told him the South’s racial situation was a blot on the whole country, and especially reflected against us overseas; and that the best way to find out if we had second-class citizens and what their plight was would be to become one of them.

“But it’ll be terrible,” he said. “You’ll be making yourself the target of the most ignorant rabble in the country. If they ever caught you, they’d be sure to make an example of you.” He gazed out the window, his face puffed with concentration.

“But you know - it is a great idea. I can see right now you’re going through with it, so what can I do to help?”

“Pay the tab and I’ll give Sepia some articles - or let you use some chapters from the book I’ll write.”

He agreed, but suggested that before I made final plans I discuss it with Mrs. Adelle Jackson, Sepia’s editorial director. Both of us have a high regard for this extraordinary woman’s opinions. She rose from a secretarial position to become one of the country’s distinguished editors.

After leaving Mr. Levitan, I called on her. At first she thought the idea was impossible. “You don’t know what you’d be getting into, John,” she said. She felt that when my book was published, I would be the butt of resentment from all the hate groups, that they would stop at nothing to discredit me, and that many decent whites would be afraid to show me courtesies when others might be watching. And, too, there are the deeper currents among even well-intentioned Southerners, currents that make the idea of a white man’s assuming nonwhite identity a somewhat repulsive step down. And other currents that say, “Don’t stir up anything. Let’s try to keep things peaceful.”

And then I went home and told my wife. After she recovered from her astonishment, she unhesitatingly agreed that if I felt I must do this thing then I must. She offered, as her part of the project, her willingness to lead, with our three children, the unsatisfactory family life of a household deprived of husband and father.

I returned at night to my barn office. Outside my open window, frogs and crickets made the silence more profound. A chill breeze rustled dead leaves in the woods. It carried an odor

of fresh-turned dirt, drawing my attention to the fields where the tractor had only a few hours ago stopped plowing the earth. I sensed the radiance of it in the stillness, sensed the earthworms that burrowed back into the depths of the furrows, sensed the animals that wandered in the woods in search of nocturnal rut or food. I felt the beginning loneliness, the terrible dread of what I had decided to do.

October 30

Lunched with Mrs. Jackson, Mr. Levitan, and three FBI men from the Dallas office. Though I knew my project was outside their jurisdiction and that they could not support it in any way, I wanted them to know about it in advance. We discussed it in considerable detail. I decided not to change my name or identity. I would merely change my pigmentation and allow people to draw their own conclusions. If asked who I was or what I was doing, I would answer truthfully.

“Do you suppose they’ll treat me as John Howard Griffin, regardless of my color - or will they treat me as some nameless Negro, even though I am still the same man?” I asked.

“You’re not serious,” one of them said. “They’re not going to ask you any questions. As soon as they see you, you’ll be a Negro and that’s all they’ll ever want to know about you.”

November 1 New Orleans

Arrived by plane as night set in. I checked my bags at the Hotel Monteleone in the French Quarter and began walking.

Strange experience. When I was blind I came here and learned cane-walking in the French Quarter. Now, the most intense excitement filled me as I saw the places I visited while blind. I walked miles, trying to locate everything by sight that I once knew only by smell and sound. The streets were full of sightseers. I wandered among them, entranced by the narrow streets, the iron-grill balconies, the green plants and vines glimpsed in lighted flagstone courtyards. Every view was magical, whether it was a deserted, lamplit street corner or the neon hubbub of Royal Street.

Black Like Me

Black Like Me